SYMPOSIUM SUMMARY

We are pleased to announce that the summary for the 2nd International Symposium on Plastics in the Arctic & Sub-Arctic Region is now available.

Our special thanks to our colleagues at GRID-Arendal and Kevin McGwin for their excellent work on the report.

Symposium summary: Day 1

Welcoming and Opening Addresses

Before introducing the host of the symposium, Pétur Ásgeirsson, Senior Arctic Official of Iceland and the Head of the Executive Steering Committee for the symposium, thanked the the Ministry of the Environment, Energy and Climate and the Ministry of Food Agriculture and Fisheries for the cooperation in organizing the event. He also thanked Magnús Jóhannesson, the Chairman of the Scientific Steering Committee and Embla Eir Oddsdóttir, Director of the Icelandic Arctic Cooperation Network, who was responsible for all the organizational details. The Nordic Council of Ministers got a special mention of appreciation for their help in financing the conference, and finally all speakers and attendees were thanked for making the symposium possible.

In the opening remarks, Bjarni Benediktsson (Minister for Foreign Affairs of Iceland) reminded us about the importance of solidarity to address the problem of plastic pollution, worldwide. In 2021, the First Symposium on Plastics in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic Region was held, and it became clear that further discussions were necessary. By hosting the Second Symposium, the Government of Iceland hopes to raise awareness, facilitate collaboration, and foster more robust efforts.

Jyoti Mathur-Filipp (INC Secretariat of United Nations Environmental Program), gave us an update on the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) process, only three days after the last negotiation meeting in Nairobi. In the face of a plastic pollution crisis, the United Nations Environment Assembly adopted the historic resolution 5/14 in March 2022, initiating the development of an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution. The third session of the INC in Nairobi marked a critical milestone, progressing discussions on the Chair's zero draft text. Over 1,900 delegates from 161 UN member states participated, electing a new committee chair and two vice-chairs. The session concluded with an agreement on a starting point for negotiation at the fourth session. The revised zero draft text will be released on December 31, and the momentum of collaboration, compromise, and commitment from Nairobi must continue into future sessions in Ottawa and Busan. The ambitious timeline aims to combat plastic pollution by the end of 2024, reflecting the strong engagement of governments and civil society in addressing the crisis.

John Aldag (Canadian Member of Parliament, on the OSCE Parliamentary Resolution on Macroplastic and Nanoplastic Pollution) provides an overview of the work of the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly (PA) work on environmental issues, particularly pollution. Aldag highlights the significance of parliamentarians in addressing environmental challenges, leveraging their power to develop legislation and hold governments accountable. The OSCE PA has a history of addressing pollution in its declarations, and Aldag discusses their resolution on microplastic and nanoplastic pollution, which was adopted in July in Vancouver. This resolution is the first to express concern about the presence of micro- and nanoplastics in the Arctic. Aldag emphasizes the importance of international cooperation, urging OSCE participating states to work towards a binding treaty to control and reduce plastic pollution. The declaration also stresses the need for funding research to advance knowledge and address gaps in understanding micro- and nanoplastic pollution.

The last address came from Eirini Glyki (Science Professional Officer, ICES) discussing the involvement of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) in various Arctic research initiatives and collaborations. ICES is participating in conferences, projects, and organizations related to Arctic research planning, high seas fisheries, and ecosystem management. Specifically in the Arctic, we are faced with applying ecosystem based management in situations where marine ecosystems are changing fundamentally and as we heard before, we face a range of cumulative impacts from human activities. The organization emphasizes a multidisciplinary and ecosystem-based approach, seeking solutions to challenges posed by changing marine ecosystems in the Arctic. ICES expresses a commitment to inclusivity by incorporating knowledge from diverse sources, including local and Indigenous communities. The message also extends a welcome to early career scientists, highlighting their importance in contributing ideas and insights to ICES initiatives.

The last address came from Eirini Glyki (Science Professional Officer, ICES) discussing the involvement of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) in various Arctic research initiatives and collaborations. ICES is participating in conferences, projects, and organizations related to Arctic research planning, high seas fisheries, and ecosystem management. Specifically in the Arctic, we are faced with applying ecosystem based management in situations where marine ecosystems are changing fundamentally and as we heard before, we face a range of cumulative impacts from human activities. The organization emphasizes a multidisciplinary and ecosystem-based approach, seeking solutions to challenges posed by changing marine ecosystems in the Arctic. ICES expresses a commitment to inclusivity by incorporating knowledge from diverse sources, including local and Indigenous communities. The message also extends a welcome to early career scientists, highlighting their importance in contributing ideas and insights to ICES initiatives.

Glyki adds: “By bridging the gap between diverse fields of study, we can then tap into a wealth of knowledge, insights, and perspectives that will enable us to develop comprehensive solutions.”

Parallel sessions on thematic discussions

Please note: An overview of the presentations from the thematic sessions will be presented in the upcoming Symposium Summary Report. The following is a summary from each of the first day’s themes.

THEME 1: Monitoring and assessment of plastic pollution in the Arctic

The presentations during the session were enlightening, underscoring a key realization: we possess a wealth of data, but the need for data harmonization is imperative. Standardizing the collection and management of data is crucial, emphasizing collaboration between scientists and industry stakeholders. The focus should shift from creating more databases to determining what data is essential and how it should be utilized.

Efforts toward harmonization should involve transdisciplinary and cross-sectoral collaboration, prompting questions about the purpose of data creation—is it for researchers or broader stakeholders? The idea of putting a price on research efforts was raised, highlighting the need to quantify and understand the economic basis of these endeavors. Drawing parallels, Normann recalled working with Norwegian fishermen who lacked routines for quantifying the downtime of their boats, a valuable metric that could be monetized.

The issue of knowledge and data sharing remains challenging, both within countries and internationally. The complexity of accessing such information was emphasized, raising concerns about permissions, collaboration, and research ethics. Temporal trends and seasonal changes were also discussed, questioning the duration required to address these trends effectively. The conversation extended to the incorporation of machine learning technologies in monitoring and the necessity for critical evaluation of data generation and dissemination methods. Overall, the discussions underscored the importance of strategic collaboration, ethical considerations, and thoughtful approaches in navigating the landscape of data in research and monitoring efforts.

THEME 2: Methodological developments to determine macro, micro and nano plastics

Reporting on the session on methodological developments in nano-, micro-, and macroplastics has been a challenging yet enlightening task. The discussions during the session provided valuable insights into the disciplined nature of plastics scientists, who adhered to time constraints, reflecting the critical importance of methodological advancements in the theme of the conference.

While the field has witnessed significant progress, the pervasive issue of plastics is relatively recent for many researchers, and long-term monitoring poses challenges. Achieving a comprehensive understanding of the current situation and identifying effective pathways forward necessitates harmonized methods across different geographical contexts. Several speakers highlighted the need for standardization and harmonization in addressing this challenge.

The complexity of plastics research was emphasized, given the diverse nature of plastic materials. The inclusion of artificial intelligence (AI) as a new method and the exploration of appropriate research methods were key points of discussion. The critical question emerged: how can we best support the development and identification of appropriate research methods?

The final point underscored the importance of making information relevant to society, policy, and other stakeholders. This aspect was deemed equally crucial as the research itself, emphasizing the need for widespread collaboration and careful dissemination of accurate information. Acknowledging the role of international bodies, the session participants highlighted the significance of coordinated efforts, with organizations like AMAP serving as exemplary leaders in leveraging expertise from diverse countries. The collective agreement emphasized the need for a united front in addressing the global challenge of plastic pollution.

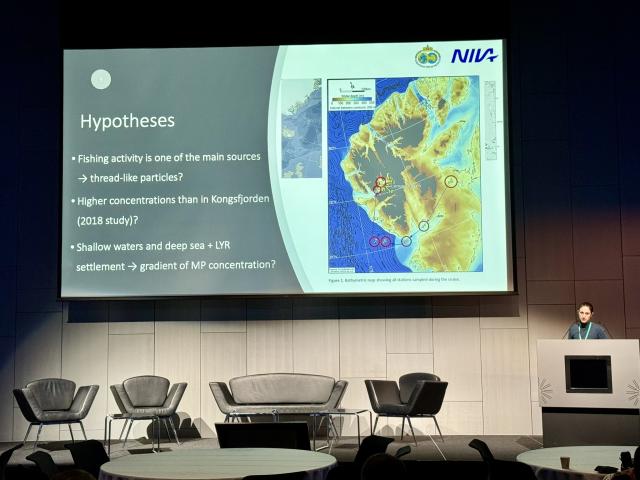

THEME 3: Sources and transport of plastic in the Arctic and sub-Arctic

To effectively address plastic pollution in the Arctic and meet policy and management objectives, a comprehensive understanding of sources and pathways is imperative. Despite its remoteness, the Arctic has not escaped the impacts of the Anthropocene and the "plastic boom" since the 1950s, evident in beach pollution, terrestrial contamination, and seabed debris.

Microplastics reach the Arctic predominantly from the EU mainland and through the North Atlantic via currents, challenging the perception of the Arctic's pristine state. The session delved into the various pathways, including atmospheric, ice, sea currents, and rivers, emphasizing the need for international collaboration in monitoring, research, and policy implementation.

Local sources significantly contribute to microplastic pollution, necessitating a focus on household waste management and the fishing industry in Arctic communities. The importance of local and Indigenous Knowledge was highlighted in addressing this aspect. Ensuring that research data resonates with policy makers, media, and the public is crucial. Utilizing various media such as articles, films, infographics, and maps can aid in effectively conveying complex information. Establishing relationships and fostering two-way discussions are integral parts of the communication process. Presenting data in ways that cater to different communities and scaling the level of research to suit the audience's understanding ensures inclusivity and active participation in discussions.

Abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG)—particularly fishing nets—poses a significant threat to marine life and to navigation. Mitigation efforts should concentrate on improving the collection and storage of net cuttings on bottom-trawl vessels and implementing proper disposal procedures in ports. Research around Iceland revealed that longlines and trawl nets, made from durable plastic, constitute the majority of marine litter on the seafloor. These materials, entangled with corals and rocks, pose a threat to vulnerable marine ecosystems (VME). This research led to the creation of a Marine Protected Area (MPA), underscoring the importance of funding and continuing investigations to leverage MPAs and marine spatial planning tools for the protection of essential ecosystems.

Addressing this issue requires consideration of cultural and social drivers, as emphasized in the Norwegian Centre against Marine Litter video shown during the opening session. A compelling message connecting waste management to people's daily lives is essential, necessitating an understanding of the underlying human-induced practices. Investigating cultural and social drivers is crucial for implementing effective waste prevention and improvement strategies.

Symposium summary: Day 2

Parallel sessions on thematic discussions

Parallel sessions on thematic discussions

Please note: An overview of the presentations from the thematic discussions will be presented in the upcoming Symposium Summary Report. The following is a summary of the second day of the symposium.

THEME 4: Impacts of marine litter in the Arctic (environmental, economic, and social)

Key findings presented by Kristian Jensen (Communications and Program Consultant, Lofotrådet)

Jensen highlighted the global nature of plastic pollution, emphasizing its disproportionate impact on the Arctic. Plastic pollution infringes on human rights. It affects our traditional way of life, our food security and our health. Plastic pollution is linked to climate change, amplifying its adverse effects in the Arctic. Jensen called for comprehensive research, data harmonization, and international collaboration for effective policies based on sound science. The unfair burden of cleaning up this generations’ plastic litter falls on our children. Jensen stressed the need for proactive communication by researchers to influence policymakers. The omnipresence of plastics challenges the notion of Arctic pristine environments, and the cost and impacts of clean-up projects necessitate careful consideration.

“Plastics are now considered omnipresent, making even the word pristine sound hollow.”

The importance of consumers’ right to refuse certain plastics and the need for limitations on plastic production were highlighted. Local Indigenous communities should not bear the sole responsibility for cleaning up plastic waste, and discussions touched on the possibility of using plastic for circular economy practices. Communicating scientific insights creatively to policymakers and acknowledging the gaps in understanding the full impacts of plastic on the environment, people, and the economy were also emphasized.

THEME 5: Arctic challenges and solutions for improved waste management

Bárðarson highlighted three main issues that came up during the discussions:

First, the pervasive issue of microplastic pollution in Arctic environments, particularly from wastewater and fishing activities, was emphasized. Innovative solutions such as gravity-driven membrane filtration and bioinspired alternatives are discussed. The importance of monitoring and addressing microplastic contamination, especially from municipal wastewater treatment plants, was underscored.

Secondly, the fishing industry’s contribution to marine debris, particularly from discarded nets and cuttings, is a focal point. Approximately 30% of beach litter in the Northeast Atlantic comes from fishing-industry waste. The need for best practices and policy solutions involving stakeholders across the fishing and agriculture industries is stressed. Successful projects, like the collaboration between Asian fisheries and Icelandic net manufacturers, were cited as examples.

Finally, Bárðarson highlighted the lack of coordination between government levels and challenges in accurate plastic sorting. The need for better systems, processes, and public education in waste management was emphasized. Art and design projects are suggested as effective tools to raise awareness, and increasing awareness among fishers about available resources can enhance recycling efforts.

THEME 6: Tackling plastic pollution: international collaboration, policies, best practices and novel developments from around the world

Nymand shared insights from discussions on plastic-pollution initiatives from local to global scales; from plastics in dental work to the efforts of the upcoming legally binding instrument on plastic pollution. Numerous efforts, from individuals to entire countries, address the issue in the Circumpolar region, resulting in highly diverse data collection. Challenges arise from these varying approaches, making analytical work complicated. Monitoring coverage varies across Arctic areas, and despite extensive data, there are “white areas” where knowledge is limited.

Estimating ocean waste presents difficulties, as plastic’s fate remains partially unknown, with invisible fragments posing challenges for detection through satellite imagery or navigation. Nymand emphasized the need to involve the younger generation in finding solutions, acknowledging the limitations of the current generation. The gap between scientists, decision-makers, and young people was highlighted, urging closer collaboration and discussion. Despite having abundant data and guidelines, Nymand stressed the importance of creating a legal framework that aligns with the lives of the younger generation. The takeaway messages emphasized the need for collaboration, shared understanding, and engaging discussions across different levels to effectively address plastic pollution. The importance of scientists adapting behaviour to connect with the next generation and allocate time for discussions with them was underlined, emphasizing the urgency of these actions for finding sustainable solutions.

PLENARY PANEL I: Conserving the Arctic

The panel discussion on Conservation in the Arctic encompassed elements such as policy frameworks, research initiatives, Indigenous perspectives and the imperative for international collaboration.

Georg Hanke (European Commission, Joint Research Centre) provided an overview of the EU’s approach to marine litter, starting with its origins back in 2008. He highlighted the challenge of policy outpacing science, noting that the EU marine-strategy framework commits its member states to monitor marine litter. He emphasized the need for effective measures to mitigate plastic production, citing initiatives such as the EU’s single-use plastics directive and regulations on extended producer responsibility. While acknowledging the challenges, he expressed optimism about the possibilities that we can implement to clean up. With the next step to implement measures, the role of continued research and funding were also addressed, as it can solve a lot of our still open questions.

Eva Kruemmel (Inuit Circumpolar Council Canada) shed light on the efforts of the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) to integrate human and indigenous rights into the plastic treaty. She called for a precautionary approach to treaties, emphasizing the reduction of plastic at its source and addressing human-rights impacts throughout the life cycle of plastics. Additionally, she underscored the impact of contaminants on the Inuit community, emphasizing the transboundary nature of pollutants. Kruemmel stressed the pivotal role of incorporating Indigenous Knowledge and voices in addressing plastic pollution, while also drawing attention to the use of information from programs like the Northern Contaminants Program (NCP) and the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP).

Susana Hancock (APECS) shared her first-hand experience encountering plastic pollution during an Arctic expedition, revealing the contrast and the shock value of seeing the problem for herself in a place with little human presence. Her discovery of nylon lines in the water and ice underscored the pervasive nature of plastic pollution in even the remotest Arctic regions. She also highlighted the importance of turning off the “plastic tap” in order to end the creation of new plastic litter, as well as of moving away from an oil-based economy. While recognizing the necessity for just transitions, enhanced management practices, technology implementation, and the establishment of consistent, enforceable policies in the Arctic, she argued that we cannot legislate our way out of this issue.

The dialogue explored the geopolitical dimension to the issue, with Árni Finnsson (Icelandic Environmental Association) noting what had been the diminishing importance of boarders due to international regimes. However, he lamented that this trend was in danger of reversing, particularly with Russia’s war against Ukraine affecting Arctic cooperation. Finnsson emphasized the need to return to the process of vanishing borders and to strengthen global cooperation in addressing environmental threats, echoing a sentiment of urgency and collaboration.

Practical considerations for addressing plastic pollution were also explored. Hanke responded to inquiries about the harmonization of methods by elucidating the evolution from early data searches to the current emphasis on specific data types that inform policy measures. He stressed the importance of understanding baselines, continuous monitoring, and identifying sources of plastic pollution both on land and in the Arctic environment.

On the topic of tourism, Hancock addressed the surge in this sector, advocating for more sustainable practices. She introduced the concept of “extinction tourism”—visiting places, such as the Arctic, that are seeing themselves fundamentally altered by global warming. She finds it imperative that the industry become less damaging.

Finnsson suggested that the Nordic Council should brand itself on environmentalism, taking a proactive stance in addressing global environmental issues. He pointed to the urgency of addressing issues such as heavy fuel oils (HFOs) on an international scale and stressed the importance of low-hanging fruits for immediate action.

PLENARY PANEL II: From Local to Global Actions

Moderator: Eirini Glyki (Science Professional Officer, ICES)

Veronica Padula (Aleut community of St. Paul Island Tribal Government and Seattle Aquarium) suggested that these ought to include initiatives that could formulate the concerns and experiences of communities and then communicate them to a broader audience in order to spread awareness of the impact of plastic pollution on people who bear no responsibility for it.

Many of these communities, she said, rely on marine resources, such as seals, and, as such, any disruption to the marine environment has an acute local impact. Messages of this sort make it clear that, while impacts may be unique from community to community, their impact is undeniable and their source must be addressed.

Peter Murphy (NOAA Marine Debris Program) found that the discussions about the issue were strikingly similar, regardless of which part of the Arctic was being talked about. Although concerning that the problem was so widespread, he found it reassuring that measures to address it in one location might be applicable in another.

In Alaska, his experience is that tailoring responses to local conditions is crucial. Equally important is not waiting too long to act. He described Alaskan communities as prepared to “give something a try” based on local observations. Even though such observations would likely be considered inadequate for action at the national level or for academics, at the local level—“where people just want to see their coasts clean”— there are lower barriers to action. For scientists and decision makers, this is an opportunity to obtain valuable data and information.

This highlights a paradox: maritime litter in the Arctic is a painful nuisance, but it is also powerful tool. Beyond catalyzing local action, it shows visitors how communities, often with a close connection to the land, suffer under pollution that has never passed through their hands.

The panel was aware that overdoing messages like this can be counterproductive. “Plastic fatigue”, as Todd Gouvin (TG Environmental) called it, needs to be prevented by mixing in messages about the gains that are being made.

He agreed the presence of plastic in the environment is a sign of failure, but, drawing on the example of the airline industry, he suggested that assessing how things had gone wrong could provide us with suggestions for how to sort it out. It is also helpful that—unlike when it comes to an issue like climate change—stakeholders are all in agreement about some of the basics of the issue. No-one, for example, believes that plastic belongs in the environment. Turning agreement into action, though, will require stakeholders speak with each other.

Ultimately, Gouvin suggested, moving the discussion forward will require changing the value we place on plastic. Everyone sees plastic as useful, but no-one sees it as valuable; the popular conception is that it is something cheap and easy to discard.

Eliminating plastic waste is often synonymous with recycling, and according to Georg Haney (Hampiðjan Group), we increasingly have no other option, as landfills reuse to accept it and incinerators to burn it.

Plastic is a product that, he said, has great opportunities for recycling, but only if done properly and with the cooperation of industry and producers of not just plastics, but also of products that contain reused plastic.

There has to be a recognition, however, that whatever works in one place might not work someplace else. Though the lessons learned in once place can serve as a point of departure for others.

He also noted that plastics is a problem that requires more than recycling to solve. As he put it “even if we change our minds completely and start recycling everything, we’ll still have a problem well into the future.”

PLENARY PANEL III: Innovative Plastic Pollution Reduction

The final plenary panel discussed various perspectives the topic. These included the experiences of Iceland’s fisheries industry, circular-economy goals, the positive impacts of wastewater recycling, and sustainable fishing practices for marine-pollution reduction.

Heiðrún Lind Marteinsdóttir (Fisheries Iceland) explained that, in recent years, Iceland’s fisheries industry has undergone a transformative revolution that has seen it go from a big source of plastic pollution to a part of the solution, thanks, in part to its collaboration with technology firms. One added benefit of this progress has been a substantial increase in productivity. The cooperation and positive intentions of fishing companies have driven the progress. Marteinsdóttir cautioned, though, that innovations hold little value for pioneers unless the companies actively embrace and test them. She believes a change of mindset is required. Many good products are already available and waiting to be used, but without adequate economic incentives, they are unlikely to become widely used.

Elin Bergmann (Cradlenet) argued that countries must establish ambitious and well-defined national goals to transition to a circular economy, along with roadmaps outlining the steps to achieve them. Otherwise, many companies may delay taking the initiative, waiting for others to lead. Numerous initiatives are emerging across various sectors, although these endeavors remain somewhat disjointed. She disagreed with Marteinsdóttir and instead emphasised the importance of governments taking prompt action. There are plenty of examples of bad products, and regulation is the best way provide the necessary impetus for improving them. No individual business can achieve circularity on its own. Collaboration is essential to progress toward a circular future, leveraging the diverse resources and strengths each brings.

Hlöðver Stefán Þorgeirsson (Water Supply and Wastewater) suggested that, when looking for solutions to problems of the sort plastics pose, the most efficient methods were likely to be found in our past, or in nature itself. In his line of business, the approach had created new business opportunities and generated additional “green” jobs, contributing to positive outcomes in multiple sectors. As an example, he noted that enhancing wastewater-recycling and safe reuse will improve water quality and availability, fostering advancements in public health, environmental sustainability, and economic development.

For Robert B. Larsen (UiT, Norway), promoting “sustainable fishing practices” stands to bring global advantages to fishermen. Full-scale trials in commercial fisheries are essential for testing and validating these practices. Using biodegradable materials as a method to reduce marine plastic pollution in fisheries promises to reduce some of the most harmful impacts, but moving forward will require involving industry, both in terms of testing, but also in order to spread acceptance.

In the end, transitioning to a circular economy will require well-defined goals, roadmaps, and government intervention, with collaboration being key to success. The collective efforts of businesses, governments, and innovators are essential for a sustainable and circular future.

Ministerial discussion

Malcolm Noonan (Minister of State, Housing and Local Government, Ireland)

As the penultimate element of the symposium, Malcolm Noonan, the Irish Minister of State, Housing and Local Government, and Guðlaugur Þór Þórðarson, the Icelandic Minister of the Environment, Energy and Climate, held a discussion that focused on responsibility for issues like nature restoration and biodiversity and the challenges associated with these goals.

Minister Noonan admitted that there were significant challenges associated with meeting these goals and that they were deeply intertwined with the broader nature crisis. “It extends beyond simply planting trees or meadows; it involves evaluating our consumption patterns,” he underscored.

The Irish government adopts an approach of “designing out” plastic waste. Success in this ares is partly a matter of exercising the political leadership necessary to put forward what, for many, will be unpopular decisions intended to induce the sort of radical behavioral change the situation demands of us – and that voters may ultimately even accept is necessary. However, even the most ambitious lawmakers need to accept the reality that, in order to see what are often long-term initiatives through to completion, they need to get re-elected, and that limits how much disruption to people’s lives they can cause.

Minister Þórðarson described plastic pollution and other environmental issues as global challenges that we all share some responsibility for addressing. Yet, despite a general awareness of the problem, there are still many things we don’t know about it, including the vast amount of plastics in the oceans. We do know that much originates from Southeast Asia, and that this must be dealt with, we do will do little to address the problem.

A collective effort is crucial, with oceans being a shared concern requiring everyone in government to add climate to their portfolio, and the public to serve as climate ambassadors.

The discussion turned to successful policies, with Minister Martin highlighting the effectiveness of bottom-up approaches from communities, as well as top-down measures, such as bag bans or taxes, to modify people’s behavior. Lawmakers need to be vigilant, however, since actions may have unintended consequences in the form of other resources being used, or industry finding loopholes that undermine their effectiveness.

Minister Þórðarson pointed to industry initiatives, like fishing-net disposal programs, as an indication that firms are aware of the importance of sustainability. Implementing a comprehensive recycling system, where producers bear the cost of pollution, encourages cleaner products. The complexity of the system necessitates more efficient mechanisms, however, including the ability to adjust the costs imposed, according to Minister Þórðarson.

Ultimately, behavioral change requires a carrot-and-stick approach. For decision makers, the focus needs to be on designing ways to eliminate wasteful elements from manufacturing processes. In reality, recycling should be the option of last resort when it comes to waste management; the focus, instead, ought to be on the right to repair, promoting durability in products that should last more than a few years (i.e. making durable goods that are actually durable). Recycling will always be necessary, but it takes an adequate infrastructure for it to be effective.

Symposium Closing Remarks

The symposium ended with an address by Icelandic Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir. She noted that the recent global negotiations on plastic pollution are a cause for optimism, comparing them with the significance of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change. Further, she acknowledged the positive steps taken by Iceland, including the national action plan covering the entire lifecycle of plastics.

Despite recognizing plastic’s valuable properties, such as durability, Jakobsdóttir highlighted the environmental consequences of single-use plastics, particularly their persistence in the environment—which is measured in centuries. A thought experiment is presented, comparing the transient inconvenience of using a paper drinking straw with the lasting and diverse impacts of a single plastic straw. Noting the longevity of plastic waste found during beach clean-ups, Jakobsdóttir reflected on the personal experience of finding a plastic bottle that was produced in the same year she was born; it yet to begin degrading.

She highlighted the environmental cost of mismanaged plastics, entering water bodies daily, and made economic arguments for addressing plastic pollution now, stating that the cost is much less than the alternative of doing nothing.

Jakobsdóttir expressed her gratitude for the work that went into the symposium and announced that a third symposium would be held, highlighting the limited time available for such critical initiatives. She concluded with an invitation to reconvene in two years, hoping for significant progress had been made in addressing this pressing global challenge before it convenes.