First Symposium Summary

The Government of Iceland in collaboration with the Nordic Council of Ministers hosted the International Symposium on Plastics in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic Region on March 2-4 and 8-9, 2021 in connection with the Icelandic Chairmanship of the Arctic Council, which took place from May 2019 to May 2021. The symposium was organised in co-operation with 11 international partners that address marine pollution in various ways. Iceland had chosen the Arctic marine environment as one of four priority areas of work for its chairmanship and addressing plastic marine litter, and in particular pollution in the Arctic, became a high priority issue in the work programme of the Arctic Council.

The Government of Iceland in collaboration with the Nordic Council of Ministers hosted the International Symposium on Plastics in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic Region on March 2-4 and 8-9, 2021 in connection with the Icelandic Chairmanship of the Arctic Council, which took place from May 2019 to May 2021. The symposium was organised in co-operation with 11 international partners that address marine pollution in various ways. Iceland had chosen the Arctic marine environment as one of four priority areas of work for its chairmanship and addressing plastic marine litter, and in particular pollution in the Arctic, became a high priority issue in the work programme of the Arctic Council.

The symposium was conceived of as a way to bring together scientists, practitioners, decision makers and other stakeholders for an exchange of information that would lay a foundation for science-based best practices that can improve the way we deal with the problem of plastics in the Arctic marine environment.

A scientific steering committee comprised of experts nominated by the partners was established to support the organising committee in setting up the agenda and selecting speakers and presenters based upon scientific abstracts.

The Government of Iceland in collaboration with the Nordic Council of Ministers were the Symposium hosts.

Symposium Partners: PAME – Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment, Working Group of the Arctic Council; Polar Institute, Wilson Centre; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP); The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES); UNESCO IOC; International Arctic Science Committee (IASC); Marine and Freshwater Research Institute of Iceland; The OSPAR Commission; UArctic; NordMar Plastic; North Pacific Marine Science Organization (PICES); GRID-Arendal, Harvard Kennedy School: Belfer Center.

This publication provides key points from the presentations and highlights from the discussions in a format that is accessible to policy makers and the general public. Recordings of all panel discussions, as well as the 55 presentations and 39 poster sessions, are available on the Arctic Council’s website.

Highlights from Day Five of the Symposium: Icelandic environment minister urges world leaders to act to stop plastic pollution

The oceans are inundated with plastics. Ideas about how to address the problem abound, but we have no time to waste.

The final session of the International Symposium on Plastics in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic Region ended on Tuesday with a call from Iceland’s environment minister for the countries of the United Nations to adopt a global treaty to prevent plastic pollution.

“There is only so much that Iceland or Arctic states or the Arctic Council can do. Marine plastic pollution is a truly global challenge, we need a global instrument to tackle it,” Guðmundur Ingi Guðbrandsson, the environment minister, said in an address during the symposium’s closing session.

At the most recent United Nations Environmental Assembly last month, many countries called for a new global agreement to address plastic pollution. Guðbrandsson hopes they will take decisive steps toward such an agreement during the assembly’s next session, in February 2022.

Much about plastic in the oceans, and especially plastic in the Arctic Ocean, remains unknown, and more research is needed. But scientists have learned more than enough to know that immediate action is required.

What they have discovered is in many ways appalling, including how microplastics make their way up the food chain to species humans consume, how discarded fishing nets slowly strangle seals and other animals, and how some birds now lay eggs that contain traces of chemicals found in plastics. The worst, though, may be yet to come: If no serious action is taken to change course, by 2040 the amount of plastic that enters the oceans could nearly triple, to 29 million metric tons a year, or the equivalent of dumping 50 kilograms of plastic on every meter of coastline in the world.

Acknowledging the contributions of the nearly 100 scientists, diplomats, and NGO leaders who spoke or made presentations during the five-day online symposium, Guðbrandsson urged decision makers to heed their message that plastics are choking the ocean.

“We need to act now, or otherwise face a future of plastics entering the marine ecosystem in a way that is difficult or even impossible to reverse,” Guðbrandsson said. “We have designed many of the tools we need. Let us act on the science. Let us act on a global treaty on plastic pollution.”

Earlier in the day on Tuesday, and throughout much of the symposium, experts expressed support for a global agreement or treaty to address growing amounts of plastic in the oceans. But some, including David Balton, a senior fellow with the Polar Institute at the Wilson Center, cautioned against letting progress on a treaty distract from other efforts to prevent plastic pollution.

A treaty, he believes, would have its benefits, but it would take many years to come into force. “We can’t assume that everything else stops while we are waiting for this as the panacea,” he said. “We need to take other actions now.”

Balton suggested moving forward to develop plastics made from organic material, such as fungi. He also called for holding an annual coastal clean-up day in all eight Arctic countries, an idea he had argued for while serving as chair of the Arctic Council’s Senior Arctic Officials. An Arctic clean-up, he said, would have the immediate effect of removing pollution, while at the same time drawing local and international attention to the scope of the problem.

Balton suggested moving forward to develop plastics made from organic material, such as fungi. He also called for holding an annual coastal clean-up day in all eight Arctic countries, an idea he had argued for while serving as chair of the Arctic Council’s Senior Arctic Officials. An Arctic clean-up, he said, would have the immediate effect of removing pollution, while at the same time drawing local and international attention to the scope of the problem.

Critics of such clean-up events often describe them as futile. Even proponents admit they are small-scale, short-term solutions. However, Julia Hager, a marine biologist, has found that they do have a long-term impact on those who take part in them.

As a guide on an expedition cruise ship that sails the waters near Svalbard, Hager organizes beach clean-ups that passengers can take part in. The activities are combined with educational sessions to inform people about where litter comes from and its impacts.

“Most travellers are shocked by the amount of plastic waste and want to know what they can do,” Hager said. “Many of them show their willingness to change their lifestyle and reduce plastic consumption.”

Activities aimed at cleaning up what is already in the ocean have their merits in other respects, too. Removing lost fishing gear is particularly important. Discarded nets make up 70 per cent of the plastics in the ocean by weight, according the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI). These nets continue to do what they were designed to do – trap fish – while also entangling birds and marine mammals. The GGGI has found that lost nets may reduce fish stocks by as much as 30 per cent. Getting old gear out of the water will also prevent it from washing up on beaches or breaking down into small pieces that are consumed by marine life.

But, with plastic production expected to almost quadruple by 2050, the solutions are more likely to be found on land, reckons Eva Bildberg of the Keep Sweden Tidy Foundation.

“We need to have commitments, and regional conventions are really important, but we have to start working with them and do what we said we would do,” she said. “I think we actually have many solutions for stopping the litter at the source, we just need to work with them.”

Highlights from Day Four of the Symposium: Looking for an Arctic approach to plastic pollution

The variety of methods scientists use to assess how much plastic is piling up in parts of the Arctic runs the gamut, from picking up plastic by hand along stretches of coast to using remotely operated vehicles to survey the floor of the ocean. In the future, if all goes well, more monitoring could be done by drones and satellites.

The variety of methods scientists use to assess how much plastic is piling up in parts of the Arctic runs the gamut, from picking up plastic by hand along stretches of coast to using remotely operated vehicles to survey the floor of the ocean. In the future, if all goes well, more monitoring could be done by drones and satellites.

There are, of course, international standards for many of these plastic monitoring methods. In the case of counting plastic on the shore, a beach should be 100 meters long, and, to get a true sense of the extent to which it is being polluted, scientists or their citizen helpers should return three or four times in a year.

In the Arctic, it is unlikely that a clean-up can – or even should – check the boxes for methods developed in other parts of the world, according to participants in the fourth day of the International Symposium on Plastics in the Arctic and the Sub-Arctic Region.

Finding a beach that is 100 meters long can prove difficult, for example. And then there is the problem of just getting there in the first place, according to Peter Murphy, the Alaska regional coordinator for the NOAA Marine Debris Program.

“In many parts of the world, if you want to go out and do monitoring, it’s as simple as renting a car, packing it up with field equipment, and going to the beach,” Murphy says. “And that's just not the reality [in the Arctic]. You have to have a lot more logistical thought that goes into it.”

Even satellites may not be as useful in the region as elsewhere, according to Lauren Biermann, an earth-observation scientist with Plymouth Marine Laboratory. This is because the sensors they use cannot see through the Arctic’s frequent cloud cover, although this is something she reckons can be compensated for by the frequency with which satellites pass overhead.

“The scientific community that is not based in the Arctic and the folks who live in the Arctic, their research questions, their concerns, and their metrics often don't match up,” she says.

“The scientific community that is not based in the Arctic and the folks who live in the Arctic, their research questions, their concerns, and their metrics often don't match up,” she says.

Liboiron analyses marine plastics that are collected by a local researcher, Liz Pijogge, who is based in Nain, Nunatsiavut. The two have realized that locals and foreign researchers want to study different things. People in the North want to know how plastics affect a species like char because it is an important source of food for them. Those from outside the region, meanwhile, prefer to look at the northern fulmar because, as a migratory seabird that is known to ingest a lot of plastic, it has been deemed a reference standard by scientific groups.

“That is not inherently bad,” Liboiron says, “but they don’t harmonize.”

For some groups that live in the region, marine plastic litter represents not just pollution but also problematic consumption patterns, marked by a shift from traditional products to plastic replacements.

“The nature of traditional products is that they wear out, and they most likely don’t leave much trace in nature afterwards,” says Gunn-Britt Retter, the head of the Saami Council’s Arctic and Environmental Unit. “We should produce quality products rather than produce waste. Right now, I think a lot of the challenge is that we have a lot of cheap and very mixed products that are easy to throw away.”

“The nature of traditional products is that they wear out, and they most likely don’t leave much trace in nature afterwards,” says Gunn-Britt Retter, the head of the Saami Council’s Arctic and Environmental Unit. “We should produce quality products rather than produce waste. Right now, I think a lot of the challenge is that we have a lot of cheap and very mixed products that are easy to throw away.”

Lauren Divine, director of the Ecosystem Conservation Office at the Aleut Community of St. Paul Island, Alaska, shares those concerns. Part of her work deals with addressing the effect of plastic on wildlife populations that people in the community consume.

“Marine litter poses myriad threats to our wildlife,” she says. These threats include animals getting entangled in discarded nets or having their habitats degraded. Ingestion of plastic is another threat, and it raises concerns about human health as well.

Addressing the problem locally, through things like beach clean-ups, is only a partial and temporary fix. Putting an end to plastic pollution will mean requiring changes from producers of plastic items – for example, manufacturers of fishing gear should make it traceable. We will also need to require that users of plastic items handle them properly – for example, fishing operations should be responsible for retrieving lost gear.

“It’s such a complex problem that we have to address the funding, the prevention, and how we’re thinking about producing and using products to really change the landscape of ending up with a bunch of litter on our shorelines that, ultimately, the community is responsible for cleaning up,” Divine says.

She accepts that we all play some role in creating plastic pollution. Like Retter, though, she believes that a different attitude towards plastic starts with different plastic products.

“There are roles and responsibilities for both producers and consumers,” she says. “But we need intentional thought towards creation of materials that are making products that will not wear out or are designed to become waste.”

Whether monitoring the presence of plastic or analysing its impact, researchers in the Arctic cannot simply adopt methods developed in other regionsThere is also a difference in research approaches between people who live in the Arctic and those who work in the Arctic but live elsewhere, according to Max Liboiron, an associate professor of geography at Memorial University of Newfoundland, in St. John’s.Highlights from Day Three of the Symposium: Apples to oranges? Scientists are having a hard time comparing their research findings on marine plastic

There is no standard method for analysing plastic pollution in the oceans – and no agreement on how much standardization is needed

If you look for plastic in the oceans, you will find it, and in alarming quantities. That much has become apparent during the first two days of the International Symposium on Plastics in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic Region. During day three, on Thursday, the discussion turned to the need for scientists to narrow down the ways they measure the plastic they are finding, especially microplastics.

If you look for plastic in the oceans, you will find it, and in alarming quantities. That much has become apparent during the first two days of the International Symposium on Plastics in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic Region. During day three, on Thursday, the discussion turned to the need for scientists to narrow down the ways they measure the plastic they are finding, especially microplastics.

The study of plastics in the oceans is a newish field. Plastics themselves only became widespread in the 1960s, and it wasn’t until 2004 and the publication of a paper titled “Lost at Sea: Where Is All the Plastic?” that the research wheels were set in motion.

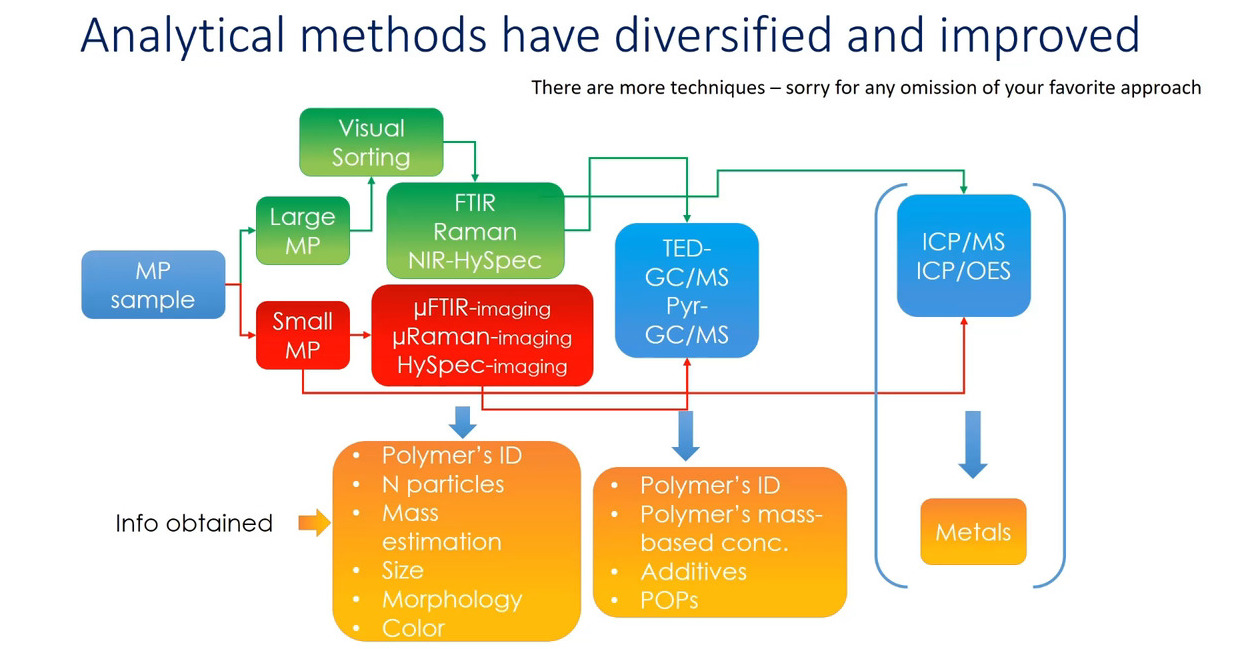

Early on, scientists primarily used one method to study microplastics in water. The method – collecting samples, separating plastics according to their density, studying them under a microscope, analyzing them with a spectroscope, and then comparing their signatures to known values – became the gold standard.

It is still used, but nowadays scientists also employ a number of other techniques for everything from the way they capture plastic to the way they determine what it is and then describe how much they have found. Jes Vollertsen, a professor of environmental engineering at Denmark’s Aalborg University, captured some of these techniques in the following flow chart that he shared during his symposium presentation, giving a sense of how diversified this field has become.

In part, the growth in the number of analytical methods reflects the fact that the more scientists learn about plastic in the environment, the more questions they want to ask about it.

“How you analyse for microplastics depends on what you want to get out of it,” says Vollertsen. He then rolls off a long list of things those in the field would like to know: source, size, shape, composition and far more.

With increasing interest comes increasing research, and with increasing research comes a growth in the number of publications. Last year, 2,000 papers about marine microplastics were published, and that 2004 paper was cited 80,000 times. But, with so much being discussed, and so few studies discussing the matter in the same way, the result has been not just insight but also confusion.

A 2019 paper went so far, according to Vollertsen, as to declare that most of the new research findings coming out of this exponential boom in publications could not even be compared to each other.

“This is still a major problem,” he says. “We cannot compare different studies.”

A part of this can be chalked up the field’s age; it takes time to come up with standards everyone agrees on. And when there is no consensus on standards, everyone believes their own preferred standards are best, scientists lament.

“We need to find one method that is pretty simple so that you can actually use it everywhere,” says Vegard Stürzinger, a marine biologist. “Right now, everybody is just doing what they want to do.”

Do we need more standardization – or less?

Not everyone agrees that divergent analytical methods are a problem, and even those who do suggest that the quest for harmonization can go too far. If one of the mantras of the symposium so far has been that “plastic is everywhere,” another is that “there is no one-size-fits-all approach” to studying it.

This is especially true when the talk turns to studying the effect that plastics have on marine life. The northern fulmar, a species of seabird whose intake of plastic is widely studied, may be as close as scientists come to having a standard, but it is by no means the proverbial canary in the coal mine that would tell us everything we need to know, according to Jen Provencher, a research scientist with Environment and Climate Change Canada, a federal ministry.

Indeed, rather than rushing to standardize a single technique for studying plastics, it is necessary, she believes, to let scientists take the approaches that best suit their ends.

“People want to know more,” she says. “There is no silver bullet. We need to think about all of the pieces and about what we want to know about in order to select the species or compartments” that are best suited to a study.

Compartments are parts of an ecosystem, and Provencher was involved in an effort to identify which compartments of the Arctic marine environment scientists should focus on when studying plastic litter. The group started with 11. It ended up with four: water, sediments, beaches and shorelines, and seabirds.

That decision disappointed those in the field who wanted to be given a single place to look, but narrowing it down even to two, Provencher argues, would have oversimplified a situation that we still do not fully understand.

There is, in fact, an argument to be made for looking at more parts of the picture, not fewer, according to Douglas Causey, a professor at the University of Alaska Anchorage who is affiliated with the Harvard University Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

In the early years of studying plastics in the Arctic, for example, most research was conducted on seabirds. Nowadays there are more papers about the effects of plastics on fish. But, Causey says, just because we are studying fish more does not mean we are studying birds less.

“We know so little about the effects of plastics in the marine environment that what is happening isn’t so much a shift from seabirds to fish as it is adding other components of the food web,” he says. There is still so much to be learned.

The symposium will resume on Monday 8 March with Day Four, when the discussion will turn to efforts to monitor plastics in the marine environment and their effects on ecosystems. The focus of the final day on Tuesday will be ways forward, with conversations about how to clean up plastics and how to prevent them from entering the environment in the first place.

Highlights from Day Two of the symposium: Plastic microfibres illustrate the challenges of fighting marine litter

Avoiding use of plastic might seem like an obvious approach, but good luck convincing fleece lovers in cold climates

Avoiding use of plastic might seem like an obvious approach, but good luck convincing fleece lovers in cold climates

Scientists have accumulated ample evidence that plastic pollution is a dire problem in Arctic waters and along the region’s coastlines, as discussed during the first day of the International Symposium on Plastics in the Arctic and the Sub-Arctic Region. Presentations during the second day of the symposium gave a sense of how challenging it will be to address the problem.

Consider just one of many sources of marine plastic litter: your clothing.

In a lot of places, clothing is something that we, for at least part of the year, choose based on its ability to keep us warm. And, depending on your fashion sensibilities, you probably prefer that it lasts for several seasons. For the oceans, that is bad news.

That’s because most of our modern winter clothes are made from artificial fibres, essentially a form of plastic that is spun into thread and woven into cloth. These fabrics provide numerous benefits: they are lightweight, quick drying, highly insulating, and remarkably resistant to wear. But those benefits come at a cost to the natural environment.

Your typical five-kilogram load of laundry releases perhaps 6 million microfibres, tiny bits of fabric that your clothing sheds while being washed. Depending on how conscientious you are (you can buy a filter for your washing machine) or where you live (some cities remove microfibres from their wastewater), the actual number of microfibres that reach the sea varies. And laundry is not the only way for microfibres to make their way into wastewater.

If cities do take steps to remove microfibres from wastewater, it can make a dramatic difference, according to Dorte Herzke, an environmental chemist and senior researcher with the Norwegian Institute for Air Research. A recent study she conducted looking at untreated water released by the waste system in Longyearbyen, Svalbard, found that its 2,400 residents sent some 21 billion microscopic particles of plastic into the adjacent fjord each year. Comparisons are hard to come by, she says, but the city of Vancouver, Canada, with 675,000 residents, which does filter its sewerage for microplastics, was found to release 30 billion particles a year — dramatically fewer per capita. In the Arctic, it is the norm that wastewater is only treated for microbial contamination, if that.

The precise source of Svalbard’s microplastic pollution is not known, but Herzke told the symposium on Wednesday that the main suspected culprit is laundry, given the type of particles she collected and that much of the release coincided with times that people were likely to be doing the wash.

Encouraging people to use different kinds of fabrics, or treating existing fabrics differently, might help reduce microfibre pollution, but she cautions that it would be a hard sell to get the people of Longyearbyen and places like it to accept lower-performing fabrics.

“We have to remember that people in the Arctic really like their fleeces and their wool to keep them warm,” she says.

Artificial fabrics, and indeed all sorts of plastic products, do what they are supposed to do on land, but once they hit the water they become a scourge.

“The question is what do you want from a fabric,” says Lisbet Sørensen, a chemist with SINTEF, a Norwegian research outfit, who has studied how artificial fibres break down. “Do you want it to be durable, or do you want it to degrade fast once the particles get into the environment?”

(Wool-lovers don’t get off the hook entirely: The dyes and other chemicals used to turn wool into yarn and yarn into clothing are themselves types of pollutants.)

The most obvious way to keep plastic out of the water is to not use it all, reckons A.N. de Vries, a resource-management specialist with the University Centre of the Westfjords. “But that’s not possible, because we are still going to need it in so many ways,” she says.

Instead, de Vries suggests addressing plastic pollution at the points where it enters natural environments. Rivers, which are big contributors to plastic marine litter because they can transport large amounts of waste of all sizes over long distances, should get particular attention, she believes.

Another approach, recommends Georg Hanke, a scientific officer with the European Commission, is for scientists to make sure that lawmakers know when a situation requires their attention, and what the costs of doing something (or not doing something) will be.

The EU already employs what he calls “triggers for action.” These, he explains, are things like threshold values that indicate when scientists believe political attention is warranted. One of the EU’s triggers, for example, is a limit of 20 pieces of litter on a 100-metre stretch of coastline. Arctic countries, he says, ought to consider setting their own limits.

“Policy needs evidence,” Hanke says. “Whatever the measure, there will be some costs, so policymakers need to be sure it is the right thing to do.”

Highlights from Day One of the symposium: Plastic, plastic everywhere

Plastic is piling up in the Arctic. Scientists are just starting to get a handle on what that means.

Marine plastic pollution is fouling the Arctic as well as posing a broader planetary crisis. But scientists still have much to learn about the problem, which a senior United Nations official on Tuesday ranked as a top global concern alongside climate degradation.

“Carried by the currents, waves, and wind, plastic pollution is found on Arctic beaches, in the water column, in the sea ice, in the sediments, in Arctic birds, in mammals,” said Inger Andersen, executive director of the UN Environmental Programme.

Andersen’s comments came during the opening session of the International Symposium on Plastics in the Arctic and the Sub-Arctic Region, organized as part of the Icelandic Chairmanship of the Arctic Council.

The symposium was originally scheduled to be held in 2020 but was postponed and then moved online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the meantime, the need to address ocean litter did not disappear, according to Andersen. Indeed, the problem, she said, has become even more urgent as vast amounts of face masks, plastic gloves, single-use food packaging, and other throwaway symbols of the pandemic have found their way into the oceans.

“We are not going to make them the enemy, we need them for COVID-19,” she said. “But this plastic waste stream threatens to negate strides that have been made in the public awareness around plastics and the fight against disposable items.”

There is no precise figure for how much marine plastic litter there is; the simple vastness of the oceans makes it impossible to know for certain, as does the wide variety of sizes, types, and locations of plastic debris. Scientists’ best estimate, however, is that there are probably 150 million tons floating around, ranging in size from giant fishing nets to microplastics, tiny fragments of once-larger items. Another 8 million tons are added each year. How much is in the Arctic is unknown, but one recent study found plastic particles in all but one of 97 seawater samples, and sea ice is known to contain extremely high levels of microplastics.

“Plastic litter can be found literally everywhere in our environment, with most of it ending up in our oceans,” Guðlaugur Þór Þórðarson, the Icelandic foreign minister, said. “We cannot continue down this road any longer.”

Focusing leaders’ attention on the plastic crisis

Iceland has made addressing plastic pollution one of the priorities of its two-year Arctic Council chairmanship, which draws to a close in May. At that time, representatives of the eight Arctic countries are expected to agree on standards that will form the basis of improved scientific study of plastics in the region. Þórðarson underscored that research is needed to identify how plastics are reaching the region’s waters.

“Knowing the extent of the problem will bring us closer to developing responses,” he said.

Although it is not possible to determine the origin of much of the plastic that ends up in the Arctic, studies of what can be identified suggest that only some of it entered the water from the Arctic. Often, scientists say, it is transported from other oceans, or, studies suggest, it is deposited there by rivers, many of which pass through urban or industrial areas.

“Plastic waste flows from rivers to the oceans; it has no problems crossing borders,” Krista Mikkonen, the Finnish environment minister, said.

This, she explained, is why the countries of the Nordic Council, which Finland currently heads, are pushing for the UN to agree on a measure that will prevent plastic pollution.

“The world is experiencing a traumatic challenge combatting plastic pollution in the environment,” she said. “Plastic pollution is global problem that requires a strong global response.”

“It’s ubiquitous”

Scientists participating in the first day of the symposium repeatedly expressed surprise at the amount of plastic that studies were revealing. “Basically, it’s ubiquitous,” said Melanie Bergmann, a marine ecologist and senior scientist with Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research.

But even as progress has been made identifying the geographic origin of much plastic litter, and, in some cases, which type of activity it stems from, scientists are only starting to understand what growing amounts of plastic litter mean for wildlife, and, ultimately, humans.

In some cases, the effects of plastic are obvious, if disturbing. One of the pictures the symposium is featuring shows a seal with a deep scar around its neck. The injury suggests that it swam into a piece of discarded fishing net as a pup. Unable to free itself, the net gradually tightened as the seal grew, cutting into its flesh. If that is indeed what happened, the seal was lucky it escaped with only a scar; getting stuck in a net can doom a seal to death by gradual strangulation over the course of several years.

Less obvious is the effect on animals that consume plastic. Studies have shown that 70 per cent of northern fulmars, a type of seabird that is common in the Arctic, have plastic in their systems. Samples of their waste indicate that the plastic they consume is not excreted.

“We know plastic is being ingested by lots of Arctic animals, but we know very little about how it is affecting the ecosystem,” said Eivind Farmen of the Norwegian Environment Agency.

Pollution prevention is key

So far, removing plastic pollution is largely limited to occasional beach clean-ups of larger items. Some work is being done to figure out how to remove microplastics from sediment, but, for now, there is little that can be done about it.

Instead, the best use of the few resources that are available for addressing plastic litter would be to prevent it from getting into the water in the first place, reckons Kine Martinussen of Keep Norway Beautiful, a conservancy.

One way to do this, she said, is to take up the matter directly with the fishing industry and owners of commercial vessels, both of which account for large amounts of plastic litter.

“We have a long list of the items of that we find. We have a sort of OK understanding of how they travel,” she said. “But we don’t know what’s happening at the littering moment, or how we can alter the routines and make sure that it doesn’t happen.”

Another thing to do: remind ourselves that, like it or not, we are all litterbugs.

“The media in Norway will sensationalize the find of a bottle from Great Britain on our shores. And that will be in the public imagination for a while,” said Martinussen. “But in Britain they will have the same article, only it was a Norwegian item.”